Moving closer together – for a better life

Creating seating areas, laying out a few raised beds and setting up a social space: it often takes just a few small steps to get anonymous neighbours talking to each other. And this also makes people more attentive to one another – they develop into ‘caring communities’. Educational scientist Annette Sprung and care researcher Klaus Wegleitner (Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Aging and Care, among others) have accompanied such communities that have emerged in Graz. The two are devising scenarios for how caring for one another can succeed, especially in old age.

However, Wegleitner is certain that voluntary work and neighbourhood assistance alone are not enough. He points out that state support should remain central and that conditions for solidarity should be legally strengthened and made fairer.

Poignant and provocative

The cabaret scene in Austria and Germany is flourishing, especially in times of crisis. But what exactly makes us laugh? Which topics are currently relevant? And what is it acceptable to joke about?

What people find amusing and what jokes they recognise as such depends, among other things, on age, gender, milieu and cultural background, reports Germanist Mario Huber. However, he regrets that the comic tradition is not so pronounced in German-language literature. "Apart from cabaret, we have television series and carnival, none of which are considered high culture. This apparently discourages authors from writing funny texts,‘ Huber speculates. Which is unfortunate, because ’humour certainly lightens the mood and can provide food for thought. Laughing together – with someone, not at someone – connects people and promotes social cohesion."

A literary view through the lens of Gerhard Roth

The Styrian writer Gerhard Roth (1942–2022), who was also a photographic artist, left behind around 60,000 photographs – ranging from everyday moments and landscapes to abstract motifs. He captured life in southern Styria as well as impressions from his travels to America, Egypt and Japan. Many of his photographs appeared in illustrated books such as Atlas der Stille (Atlas of Silence) and Über Land und Meer (Over Land and Sea) or other publications such as Im unsichtbaren Wien (Invisible Vienna) and Spuren (Traces).

The Franz Nabl Institute for Literary Research at the University of Graz has digitised around 40,000 photos from 1977 to 2017 and tagged them with over 200 keywords. The digital photo archive, including information about Gerhard Roth and his works, is available at gams.uni-graz.at/roth. Due to data protection restrictions, a password is required, which can be obtained from the collection manager at daniela.bartens(at)uni-graz.at.

An interview with Gerhard Roth from 2012 can be found in UNIZEIT magazine.

Palliative work: thinking through to the end

What do people need at the end of life - beyond medical and nursing care? The philosopher and former nurse Patrick Schuchter is working with his team on the FWF project "Philosophical Practice in Palliative Care and Hospice Work" to investigate how philosophical practice can provide support for the dying, their relatives and carers.

The conversations with the people concerned are about exploring life questions together: Have I lived well? What is important? What comes after death? The participants found the conversations inspiring and relieving. "Obviously, it's not just the body that needs to be cared for, but also the spiritual being cultivated," summarises Schuchter.

The project team is currently working on proposals on how philosophical practice can be integrated into the health and social care system.

Reading between the lines

Medieval glosses - marginal and interlinear notes in manuscripts - analysed Bernhard Bauer from the Department of Digital Humanities to investigate language contacts and the transmission of knowledge in the early Middle Ages. Among other things, he is focussing on Old Irish, Old Breton and Old Welsh annotations in Latin works such as Priscian's grammar or Beda's calendar treatise. Bauer is particularly fascinated by personal notes by Irish scribes about their everyday lives: "Interestingly, such personal information can only be found in Irish notes."

Thanks to digital facsimiles and automatic text recognition, it is now possible to transcribe efficiently, but some details still require work on the original. The aim of the project Glossit project is to make the paths of knowledge and multilingualism visible. "The glosses show how scholarly communication worked back then - often across language barriers," says Bauer.

Caught in the war

Thirty years after the genocide in Srebrenica, Serbia and the Republika Srpska still lack the political will to come to terms with the past. Nationalist narratives and the instrumentalisation of memory prevent reconciliation and deepen the division in society. Civil society initiatives such as "Women in Black", Documenta in Zagreb and the former Research and Documentation Centre in Sarajevo offer hope. They are committed to education and dialogue across ethnic boundaries. "We need to support these forces," says historian Heike Karge. In her teaching and research, she has been committed to international cooperation and remembrance work for years. She particularly emphasises the importance of civil society work, which "invests a great deal of energy in asserting its position against nationalist agendas". At the same time, Karge sees major challenges posed by a lack of prospects, emigration and a lack of access to European exchange - problems that place a heavy burden on the future of the region.

Language barriers in everyday life

How communication can work in a multilingual society is the subject of research by Şebnem Bahadır-Berzig, Professor of Translation Studies. She is focussing on people who have received little attention in research to date: "In everyday life, it is often children or volunteers who ensure communication. However, too little consideration is given to their needs and reliability." Some children are annoyed or stressed or - they make fun of it.

This is particularly problematic in legal advice for refugees and in healthcare: ‘In these very precarious situations, the fact that the quality of the interpreting must be just as high as that of the counselling is obviously overlooked,’ criticises Bahadır-Berzig.

Students can attend courses to prepare themselves for interpreting in emergency or crisis situations, learn to be aware of their own resources, maintain personal boundaries and not neglect self-care.

African Studies

The hunger for raw materials and migration movements are increasingly focussing attention on Africa and changing the Western perspective on the continent. As much as interest in African countries is growing, our perceptions of them are still vague, and in many cases persistent prejudices remain.

Linguist Jennifer Brunner and cultural scientist Angelika Heiling are working on closing knowledge gaps with the ‘African Studies’ module series and establishing an African Science Hub in Graz.

Brunner, who is primarily concerned with the languages of Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania, emphasises the well-functioning communication - for example, around 500 languages are used in Nigeria alone, and yet communication still works.

The African Studies module series is offered by treffpunkt sprachen at the University of Graz. It provides an overview of the extraordinary diversity and dynamics of languages in Africa and gives a flavour of literature, art and culture.

Digital puzzle game - putting together a 1500-year-old altar slab

Passionate puzzle players are in demand. The task: to reassemble a 1500-year-old marble altar slab that has been broken into many small individual pieces and was part of the furnishings of the early Christian bishop's church in Lavant/East Tyrol. The particular challenge: not all of the fragments are still there and the remaining fragments are chipped.

After archaeologists had made several attempts to reassemble the fragments since the 1950s, new paths have now been taken: The fragments were restored and digitised under the direction of archaeologists Stephan Karl and Paul Bayer. Together with Reinhold Preiner, computer scientist at Graz University of Technology, a digital puzzle game was created. The players are not working alone, but simultaneously and together with other interested parties from the entire population, because "people who are not experts in the field bring in new perspectives. A project like this also offers the opportunity to get people excited about science and break down inhibitions," says Karl. This type of science education - "open reassembly" - could be used in museums "to make archaeology a lively and playful experience."

Anyone who wants to join in the puzzling has the opportunity to do so here.

The digital puzzle game made a really big appearance at Buch Wien (20-24 November 2024): Visitors to Austria's largest book fair were able to find out more about the exciting project in the Science Lounge under the motto "Together against science scepticism". And especially for a young target group (children and young people), the workshop "Mitforschen: Gaming 4 Science" workshop was on the programme.

Critical thinking as a way out of the impasse

Climate change, social division and authoritarian political developments are just some of the huge challenges of our time. To overcome them, we first and foremost need an awareness of the ideas and convictions that have brought us there, translation scholar Stefan Baumgarten is convinced. He would like to see radical thinking, "critical, wild and open". Which also means thinking in a complex way, incorporating science, empathy and emotions instead of polarizing. Musicologist Susanne Kogler follows on from this and emphasizes the importance of self-reflection as a major contribution to critical practice. It is important to shed light on how thought patterns and ideologies shape our perception and how our perception can promote or prevent critical thinking.

The two researchers have launched the research project "Radical thinking in the Anthropocene" initiated.

Visible history

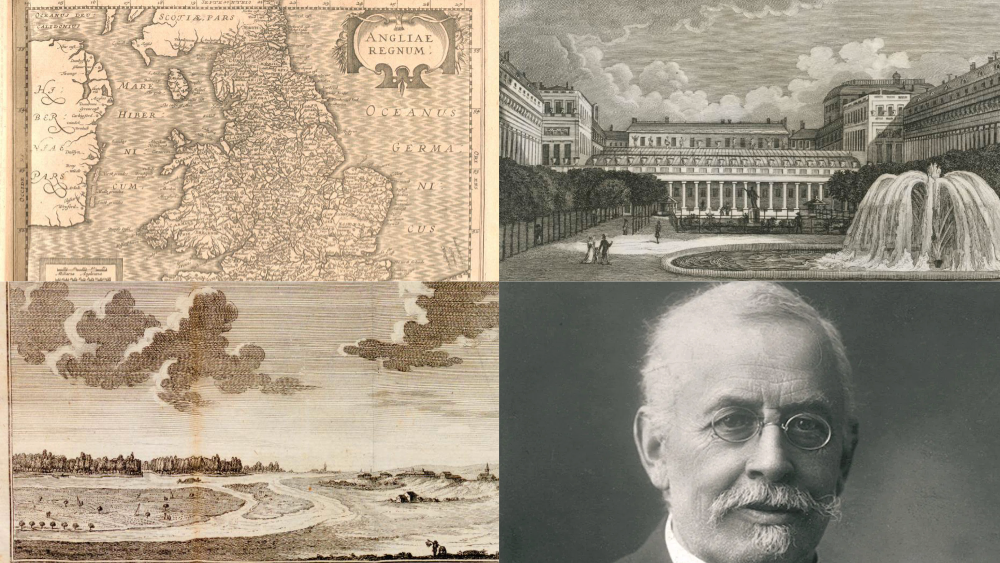

Old atlases, unique city views, secret letters and valuable scientific documents from the collections of the University of Graz were meticulously digitized and made technologically fit for the future.

Financed by funds from the Federal Ministry of Culture and Sport, in 2023 the Department of Linguistics and Department of Digital Humanities, the University Archive, the University Museums and the University Library's special collections joined forces in 2023 to secure some of their historical collections for the long term as part of the "Kulturerbe digital" project. The objects were scanned, enriched with metadata and published on various ➡ online platforms.

55,000 works are now available to the general public and reveal a piece of cultural identity.

Do we still need translators at all?

Thanks to Google Translate, DeepL or ChatGPT, communication barriers can be overcome at the click of a mouse. "The results sound good and are becoming increasingly useful. However, the programs learn almost exclusively from human translations," emphasizes Michael Tieber, university assistant at the Institute of Translation Studies. And this is purely a computational achievement, because "the programs don't know what they are doing. They have difficulties with phenomena that do not occur in the training data," explains the researcher. Content deficits, incorrect or inappropriate terms in the context are therefore not uncommon.

What is the best way to deal with the machine translation offer? Getting a translation suggestion is not a mistake. "But as a human, I have to be able to assess how far it can be used and where it needs to be changed," the researcher explains. Translating is not simply a matter of exchanging words; in addition to the correct technical terms, it is also about the style, which must fit the situation. So it's also about empathy.

The University of Graz is in the process of adapting its curricula and integrating digital skills and translation technologies to a greater extent. "At the same time, we want to convey the awareness that humans still offer great added value compared to machines," explains Tieber.

Can artificial intelligence create art?

AI is able to write texts, take photos, paint pictures and compose music. But is that still art? "Yes, even if it is hotly debated," says musicologist Susanne Kogler. "Artists react to their environment, take a critical look at their time and also explore the limits of technical possibilities, at least according to an avant-garde understanding of art." It is their task to work against the mainstream, to break habits, to go beyond the boundaries of tradition

Accordingly, Kogler also wants to make the possibilities of the new digital tools the content of courses. The tools need to be used in a targeted manner and the results generated by the AI need to be assessed correctly. However, the researcher takes a critical view of automatically produced works, such as those already used in the entertainment industry: "Progress and innovation cannot be achieved without human intervention," Susanne Kogler is convinced.

More competent with AI

Automated translation programs can make living together easier, Boban Arsenijevic is convinced. The Professor of Slavic Linguistics is an expert in computational linguistics and is working to improve the skills of graduates.

"Even free AI systems make it easier to access information because they can translate content into a wide variety of languages. They are also always available and much faster and more efficient than humans," summarizes Boban Arsenijevic.

The researcher himself is working on teaching such automated tools to speak correctly (see UNIZEIT 1/2020). He sees great added value in the machine: "Artificial intelligence is able to analyze large amounts of data, extract patterns and make data-based predictions. It thus enriches multilingualism in a way that we humans would not be able to do."

However, the Slavicist not only trains machines, he is equally concerned with the contemporary education of his students. And he emphasizes the importance of problem-solving skills, critical thinking, data analysis and management skills.

Learning made easy

"The right environment and simple, clearly laid out documents help tremendously," explains Elke Höfler, Assistant Professor of Media and Language Didactics at the Institute of Romance Studies. The human brain has a limited "working memory", and any kind of distraction - including not only the party in the neighboring apartment, but also lavish formatting, useless graphics or irrelevant additional information in the script - uses up capacity that is then lacking for learning.

To increase retention and deepen understanding, Höfler recommends involving as many senses as possible: "Reading a passage from a script out loud while standing on one leg or a balance board or while walking can help, as long as you feel comfortable doing so." Handwritten notes are more suitable for the library than gym exercises. "The movement of the hand stimulates the brain, and we usually summarize the essentials," says the researcher.

There are also a number of advantages to learning in groups: if you ask and answer questions and discuss the content, it sticks faster. Alone, you are efficient when you actively approach the material. "Underlining, summarizing, drawing mind maps or infographics creates cross-connections and helps us retain what we have learned better," explains Höfler. She provides detailed tips, including scientific explanations, on her blog Digitalanalog.

Nameless ancient texts as promising sources

"We see the reception of ancient works through a very narrow lens. What is preserved is what was passed on in the schools of the imperial period and late antiquity and copied in the writing rooms of medieval monasteries," says Markus Hafner. However, this is only a narrow slice of reality, which primarily takes into account the patriarchally dominated society.

As part of a project for which he recently received a prestigious Starting Grant from the European Research Council, Hafer is working on anonymous texts such as graffiti, proverbs and jokes. These reflect the diversity and colorfulness of antiquity and give space to previously unheard voices.

Is equal fair?

Right-wing populism presents it as an ideal: a society in which everyone has the same values and norms according to which they judge what is right and what is wrong. Where the "normal" is the measure of all things and people with "different" needs and desires have no place. But how does this concept fit in with the principle that all people have the same value, enjoy the same rights and are allowed to make the same demands? A thought experiment with the philosopher Elias Moser.

Cancel Culture only exists in social media

Readings by drag queens would endanger our children. Gendering is for nothing. And a very narrow definition of what is normal. Society once seemed more open. Are we moving backwards again?

Historian and cultural scientist Heidrun Zettelbauer denies this Heidrun Zettelbauer. She argues that the sometimes acrimonious debates do not reflect the attitude of the majority of society. Rather, it is a "culture war" proclaimed by certain political groups, which is mainly being waged in the social media. This has little to do with the analog world; here - in our manners, in broad political exchange or even in the cultural sector - the picture is different. Heidrun Zettelbauer ultimately emphasizes the opportunity inherent in a democratic society to negotiate what we can or want to talk about and how.

Intermediate tones

How much does language influence our view of the world? Can we really only perceive what we have words for? And does our diverse ability to express ourselves make us smarter?

People who speak several languages usually also have a better understanding of other cultures because she or he is used to communicating with people from different backgrounds," summarizes linguist Hermine Penz. Multilingualism increases both our creativity and our ability to engage with unfamiliar situations. It also changes our view of the world, because every language works differently and can therefore never be translated one-to-one into another.

To the article (in German)

Word treasure

The Lower Austrian government's plan to make German compulsory in the schoolyard made headlines at the end of March and showed again: Multilingualism is often seen as a shortcoming in Austria when it comes to people with a first language other than German. But the advantages outweigh the disadvantages if you know how to use them, explains Barbara Hinger.

To the article (in German)

Dystopian visions

Books, monitors and screens are mirrors of reality: Fictional works have always shown "where we are as a society and where we might be headed if we carry on as before," says Stefan Brandt, a literature and cultural studies scholar at the Institute for American Studies.

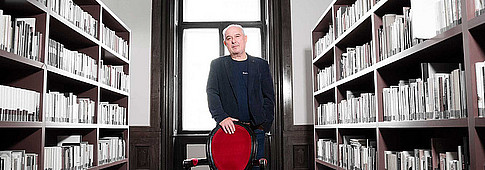

And for the most part, these scenarios look pretty bleak. "From the second half of the 20th century on, there are hardly any positive images of the future in fiction," confirms Klaus Kastberger, director of the Franz Nabl Institute for Literary Research.

But why is that?

To the article (in German)

Learning and teaching about democracy

There is no such thing as an ideal or correct democracy. Democracy is always in motion. Those who take up this challenge in the classroom must therefore not shy away from uncertainties, must relinquish interpretive sovereignty and power and the prerogative of interpretation, and must allow for a change of perspective.

"In Austrian textbooks, the subject of democracy is still presented as the educational project of a male, white elite from the Western world. It is depicted as a success story from the point of view of the victors," says historian and educator Christian Heuer. Others stories remain mostly unheard - there is hardly a word about or from migrants, workers or women.

To the article (in German)

Fear of aging

An international research team shows how nationalists in Southeastern Europe profit from negative images of aging

Every country in southern Europe has its own challenges to contend with. But one collective fear unites them: the fear of aging. "Because people are living longer and longer and the young are increasingly migrating, the narrative has emerged that entire nations are threatened with extinction," says historian Florian Bieber.

Ulla Kriebernegg of the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research on Aging and Care adds, "Old age is often portrayed as a danger in this region as well. Not only in political contexts, but also in everyday language; in artistic representations, however, alternative images of old age often emerge."

To the article (in German)