You are studying German Studies and are also a student assistant at the Institute of German Studies. Do your expectations of this degree programme correspond to reality or has everything turned out quite differently than expected?

I had very different career aspirations at the beginning of my studies than I do now, so that has changed completely. However, I would say that I had different ideas about myself as a person rather than really having different ideas about the degree programme. Before I decided in favour of German Studies, I used the curriculum to help me decide. I therefore had ideas about the structure of the degree programme which, in my opinion, corresponded to reality. In terms of content, it's just so much better than I expected...

When people hear German studies, most people think of literature (science) first. What brought you to linguistics?

My enthusiasm for grammar was awakened in the lectures in the first semester when I realised that you can't put word types or sentence structures, for example, into a strict scheme like the one taught in German lessons at school, but that there is so much more to it than that. The language is just so fascinating! The deeper you delve into it, the more exciting it becomes, because you can think about very different contexts. So you could say that being introduced to analysing language as a whole as well as individual phenomena in various courses led me to linguistics, because that's where the foundation for my interest was laid. I don't know if I would have become so interested in language without them.

You run the debating club at the Institute of German Studies. What exactly do you do there and how can the members of the club benefit from it?

I am the moderator and logistical supervisor of the debating club, which means that my tasks consist of planning the events and (unsurprisingly) then moderating them. This begins with the search for a suitable topic, as our events, which are generally held once a month, focus on a specific topic, whereby both German studies-specific and current topics from other disciplines are selected. I then find experts from the respective subject areas, who then open the event with a keynote speech. I use various advertising channels to reach as many interested parties as possible. As not only German studies students are welcome, but also participants from all other subject areas, part of the benefit is that you get a very diverse and interdisciplinary input in this way. You also meet lots of people in a relaxed environment and can therefore network well. One of the things I appreciate most about my job is the knowledge building: I have significantly more knowledge after each event than before.

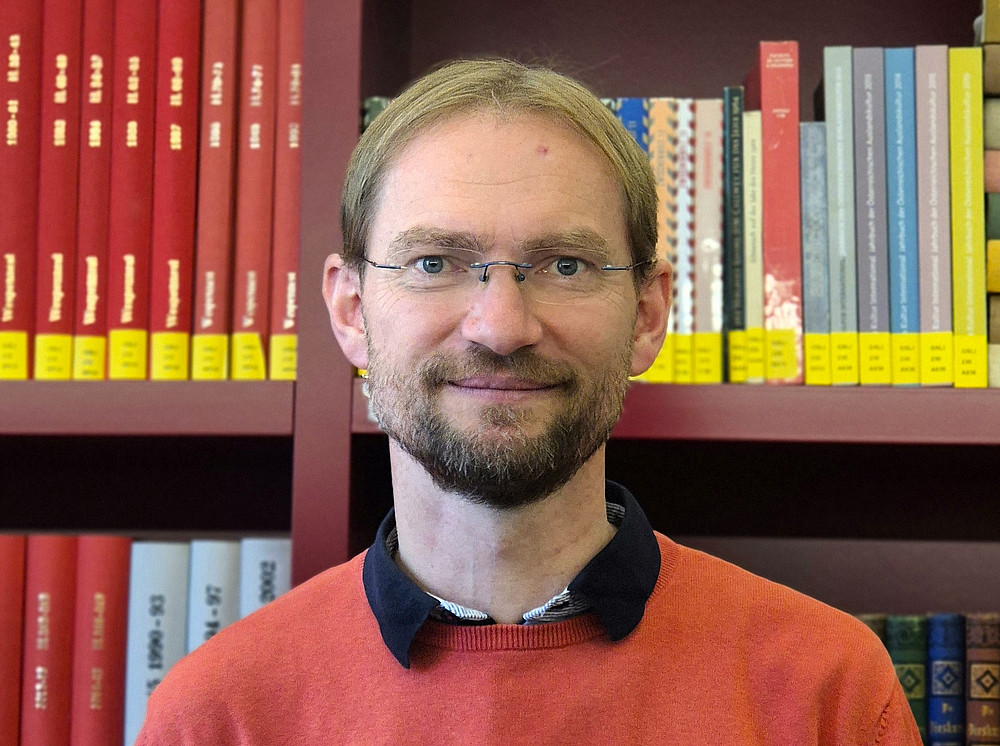

The library of the Franz Nabl Institute for Literary Research contains around 23,000 volumes, for which you are responsible. What are your main activities here?

In the library, I am responsible for borrowing and returning books as well as supporting students and researchers in their searches for suitable works from our collections. In addition to books and journals, this also includes the literary bequests and estates from our archive. It takes a lot of time to inventory journals, some of which I then have bound in a bookbindery before they are put on display here. I make sure that we have as complete a collection of journals as possible, which is not always easy. I also look after the homepage of the Franz Nabl Institute and the general e-mail address of the Literaturhaus Graz.

What is the best and most challenging thing about your work?

My favourite thing is meeting all kinds of people who come to the library because of their love of literature or the history of the country. I share their joy when, for example, I can provide crucial information for a seminar paper, help someone make an unexpected discovery or find a long sought-after poem. On the other hand, it is annoying when books are not in their place or are not where they are supposed to be. Then a sometimes lengthy search begins. One of the difficulties is also finding enough space for all the books. I have to move them back at irregular intervals to make room for new acquisitions.

Are there any books that you would not want in the library?

I don't want to include any books by National Socialist authors in our collection. That would attract a reading public that I don't really know what to do with. I much prefer the new fiction publications from Austria, which I also enjoy reading privately.

Did you always know that you wanted to become an ancient historian or did you initially come to university with a different study programme in mind?

I originally studied a combination of classical archaeology and art history, but I quickly realised that knowledge of the historical background was essential for a better understanding of the material legacy. That's how I came to ancient history. It was in this subject that I ultimately completed my doctorate and habilitated - a decision that I have never regretted because it gave me the opportunity to turn my hobby into a career.

What is important to you in teaching and what do you particularly like about it?

I have to admit that at the beginning of my career, I wasn't sure whether teaching, which is an important part of the profession, would really fulfil me. However, the longer I taught in front of students, the more I realised how important teaching is. This applies not only to the educational or human-social aspect, but also to research. On the one hand, it is simply a great experience to teach young and inquisitive people something that will then accompany them on their further life and career path, but on the other hand, the exchange with students in the context of research-led teaching also offers the opportunity to look at things from a different perspective on the basis of the discussion, which in turn can be an impetus for your own new ideas.

What are you currently researching and what fascinates you most about it?

I am currently devoting a lot of time to researching the phenomenon of "just war". When looking at ancient issues, you often have to rethink things. Unlike in modern times, warlike events were the order of the day, while a period of peace was the exception. This means that when analysing topics such as "war", "violence" and "justice", one must detach oneself from recent ideas and engage with ancient lifeworlds and values in order to arrive at a reliable reconstruction of past events. The focus is therefore on questions such as: What was understood by a "just war" in antiquity? What means and media were used to underpin and spread this ideology/ideologies? In what form do these world views continue to have an impact to the present day?

Psycholinguistics is also one of your main areas of research. What does this field of research involve?

Psycholinguistics is the research area of linguistics that deals with language as a cognitive system, i.e. how language is processed in the human brain. Experiments are often carried out in psycholinguistics to find out how linguistic knowledge is structured and which cognitive processes take place when we hear, understand and produce language, both orally and in writing. Speaking and understanding are highly complex processes that we are (usually) unaware of.

You also specialise in Philippine languages, among other things. How did you come to do this and what fascinates you about it?

Our Institute of Linguistics in Graz and the linguistics degree programme here focuses on typological research and non-European languages. This is what I find particularly exciting about my field of science, as it allows us to familiarise ourselves with, research and compare language systems that are structured extremely differently and have developed and are used in very different cultures. The majority of the world's 6,000 to 7,000 languages have not been written down. There are many fascinating things to discover in each of these languages, and I discovered the Filipino languages more or less by chance. Their grammar is very special. The time I spent in the Philippines during my research stays was very enriching. Dealing with cultures, but also with language systems that are completely different from German, English or Italian, for example, opens up completely new perspectives.

What would you recommend to someone who is considering studying linguistics?

Of course, you should like languages and find them interesting. However, linguistics is not a degree programme in which you learn foreign languages, but one that requires a lot of analytical and sometimes mathematical thinking. Linguistics is very interdisciplinary and differs from most other humanities subjects - to the surprise of some first-year students - in that its research methods are influenced by the technical, natural and social sciences. You should definitely have a certain interest in this subject.

As with any degree programme, it is of course essential to be open and curious and to want to discover the unknown. Then you will certainly not be disappointed with us.

Elke Höfler

Assistant Professor of Media Didactics and Language Didactics, Department of Romance Studies

You are Assistant Professor of Media Didactics and Language Didactics. What do you think is the special significance of didactics, especially media didactics?

Didactics, and media didactics in particular, are at the centre of the question of how content and skills can be taught effectively using suitable media. Its particular relevance lies in the fact that it not only picks up on technological developments, but also critically scrutinises them and integrates them in a pedagogically meaningful way. In an increasingly digitalised world, it makes it possible to make education more inclusive, interactive and flexible without losing the importance of reflection and personal interaction. The dovetailing with language didactics in particular shows how media can promote linguistic and cultural competences, as language is also a medium.

You also work intensively in areas such as artificial intelligence and social media and also run two blogs that deal with didactics, language and digitalisation. To what extent do social media, ChatGPT and the like influence teaching and learning behaviour?

Social media and AI tools such as ChatGPT are changing teaching and learning behaviour quite a bit, as they enable new forms of interaction and collaboration and demand critical thinking in dealing with the disseminated content. Attention economy is just one keyword here: everything has to be quickly grasped in the age of social media, you scroll through timelines, you perceive a lot of things unconsciously without consciously scrutinising them: is the information true or false? Up-to-date or long outdated? Is it created by humans or artificial intelligence and their respective biases? These technologies also change reading and learning behaviour, which we should take into account in the classroom.

On Twitter (now known as "X") you often use the hashtag "#edupnx" what's it all about? What are educational punks?

The hashtag #edupnx stands for "education punks", a movement founded by women in the education system that rethinks education in an unconventional, creative and courageous way. It is about questioning traditional teaching methods, promoting innovative approaches and bringing education closer to the realities of learners' lives. The Bildungspunks community inspires each other by sharing ideas on platforms such as Twitter ("X") or Bluesky in order to provide new impetus for schools, universities and further education. The hashtag symbolises this open, experimental and often unorthodox approach.

Why did you decide to study linguistics and would you do it again?

The decision to study linguistics was initially made without a plan and more with the idea that I was interested in learning languages. Looking back, it's strange because the actual learning would probably have been more involved in another course, such as translation studies, but I don't regret it. Understanding the structures of languages, how they work, getting to know overarching commonalities: that is also very exciting for me and actually sometimes helps with language learning itself. That's why I would definitely choose linguistics again, albeit with a better plan for my future.

What was the most fascinating course for you?

For me, the lecture and the proseminar on historical linguistics were definitely a turning point. In the first two weeks we were shown that there are laws by which languages evolve and by which you can get back to a language level that was spoken centuries or even more than a thousand years ago. I love finding such regularities and connections, but I also like the idea of building a special relationship with people who lived a long time ago.

As a linguist, which language do you find most exciting?

The more I know about a language, the more curious details I know and the more exciting I find it. I love learning about German, whether it's grammatical rules that explain my own use of the language for myself or the historical development of German. But I've always wanted to learn a language that doesn't use the Latin alphabet and have now been learning Chinese for two years, a language that not only has a lot to discover within the linguistic system, but is also part of a completely different culture. I couldn't say that I find one more interesting than the other, but there are very different reasons for my interest in each.

You are particularly interested in European-Jewish literature and Russian as a Jewish language. What constitutes a Jewish language culture? What can we imagine it to be?

Since the Jewish Enlightenment, the Haskalah, which developed in Europe from the late 18th century and aimed to open up the Jewish world and at the same time emancipate the Jewish population, completely new possibilities arose for Jewish literature in terms of themes, motifs and interactions with other literatures. This also affected the language - modern Jewish literature was now written in a wide variety of languages, whether it continued to be in Hebrew, Yiddish or Ladino, or whether it was now also in German, Russian, Polish or English. The choice of language thus touched and still touches on processes of perception, interrelationships, translation and migration, etc., as we currently encounter in the confrontation with increasingly global societies. Social, historical and cultural developments, challenges and questions are thus intertwined in Jewish language culture.

What does it actually mean to be a lecturer at the university?

For me, it is a great privilege to be able to work with young, interested and critical people on a daily basis, who go through the world with open eyes and ears and from whom I can also learn. The nice thing compared to school is that the students have decided to study themselves and therefore already have an interest in the subject as such - you just have to treat them with respect and enthusiasm for your own subject.

What fascinates you most about English linguistics?

I not only teach linguistics, but also cultural studies, and with these two areas you can cover a very broad spectrum - from core linguistic topics to critical media analysis and topics such as neocolonialism and stereotypes, everything is included. As it is important to me to offer students something that can be relevant for their future, these two areas combined are the ideal vehicle for me to introduce them to important phenomena and contexts in today's world, which is still dominated by English-speaking countries and their Eurocentric ideologies.

What was your best moment as a teacher?

There are many, but in general it is always a great moment for me to look into a group of interested eyes and to see in discussion groups that students dare to express their own opinion, even if it does not correspond to the majority consensus. Even if in many cases - perhaps depending on the time of the course, I hope - the tired eyes are sometimes in the majority.

How long have you been working at the Faculty of Humanities/Department of History?

I've been working at the Faculty for almost 33 years now. First as a young typist, when there was still a lot of writing to do, then as a department secretary and now as an institute secretary or office manager, as it is now called.

What is the strangest thing you have ever experienced in your job?

So many strange, weird and funny things have happened. If I had known that I would be here for so long and that everything would happen here, I would have written it all down and it would fill a book. Hardly anyone believes what happens sometimes.

Is there anything you would particularly miss if you were no longer working here?

The huge variety of people. The nicest, but also the weirdest people from home and abroad from all age groups come to me. And I hope that even after 33 years I can still help them in a friendly but firm manner. After all, that's why I'm here!

What does a cultural anthropologist actually do?

As a cultural anthropologist, I deal with the relationship between humans (Greek anthropos) and culture. First and foremost, I ask the question: What is understood by "human" and what is understood by "culture" in the past and present, in different contexts of use and societies worldwide? This fundamental conceptual work goes hand in hand with the question of how people organize, shape and endow their lives and coexistence with meaning. The development and meaning of images, narratives, writings and modes of action are just as much of interest as the production and use of things, techniques, buildings and cities or the treatment of animals, plants and topographical features such as mountains or bodies of water. In short, cultural anthropology explores what makes us human and assumes responsibility for the peaceful coexistence of all inhabitants of the earth.

You also conduct research into art in public spaces. What do you find particularly interesting about this?

I also studied art history and visual arts education, worked in museums and schools and in my research and teaching have always dealt with the productive interfaces between cultural anthropology, art and educational work. The so-called "art in public space" represents a field of research in which these areas overlap in a dense way. Overlapping with my research focus on urban anthropology, I am particularly interested in urban settings for "participatory art projects", in which artists make aesthetic statements in urban space with the participation of city residents and visitors. Examples that I myself have been involved in include the art projects "No monuments. On the history of work and immigration" (artist: Kristina Leko) or "Because there are so many" (artist: Elisabeth Schmirl). Here, very different ways of imagining and perceiving the city and society come together, the cultural analysis of which can contribute to an understanding of significant social issues of the present.

What is particularly important to you in teaching? What would you like to pass on to your students?

In addition to teaching the basics of cultural studies in a way that is as stimulating and realistic as possible, I would like to allow students to participate in finding and working on my own research topics in the sense of research-led teaching. It is important to me to sharpen students' research skills both in the lecture hall by reading and discussing academic texts and in the form of field exercises on site - especially in urban areas. In particular, I would like to convey to the students on their professional path that the differentiated collection, presentation and circulation of knowledge is not only an exciting and enjoyable task, but above all one with a high level of social responsibility.

One of your main areas of research is film music from the 1930s to the 1960s. What do you find most exciting about this topic?

For me, the 1930s and 1960s are a particularly exciting time of comprehensive media and aesthetic change: ultimately, the foundations for film music as we know it today were laid during this period. The international acceptance of sound film technology around 1930 offered new possibilities for music in audiovisual contexts - until the end of the 1960s, playback and recording technologies in the field of film music also improved continuously. At the same time, this period is also eventful politically, economically and socially in a global context.

It is therefore particularly exciting for me to see how film music fits into the complex context of this period. In the field of music, this is characterized on the one hand by the aforementioned technological innovations, while on the other hand, film composers at this time still place themselves strongly in a traditional historiography of art music - and this in the context of Hollywood films geared towards entertainment and profit.

They are leading the FWF research project "GuDiE", which operates at the interface between musicology and digital humanities. The aim is to create a digital edition of Gumpenhuber's theater chronicles. What does this mean?

In the mid-18th century, ballet master Philipp Gumpenhuber was commissioned by Maria Theresa to compile an overview of all the activities of the Viennese court theaters. Gumpenhuber's chronicles therefore record all the details of theater life at the Viennese court in the period 1758-1763: this includes information on the operas, ballets and plays performed, but also information on rehearsals and details of mishaps in theater operations, such as changes to plays due to illness.

Today, however, Gumpenhuber's chronicles are separated by the Atlantic: some of the surviving chronicles are in the Houghton Library at Harvard University and others in the Austrian National Library. The digital edition (Gumpenhuber Digital Edition; GuDiE for short) has set itself the task of reuniting the chronicles in the digital space and supplementing them with innovative visualization options. In future, it will be possible for interested members of the public to see what was performed at which theater in Vienna, when, with which actors and at which theater. Anyone who has ever wondered how an opera performance was rehearsed in the 18th century or which aristocrats from other courts were guests at the Viennese court on which occasions will also find what they are looking for at GuDiE.

What advice would you give to young people who are considering studying musicology and what do you think makes Graz a special location for research in the field of musicology and the arts?

Just try it out and let yourself be surprised! "Musicology" is an unwieldy term that is difficult to get your head around at first. However, I am convinced that those interested in music will hear supposedly familiar things with new ears when studying musicology. As a tip: try consciously listening to the music the next time you're watching a Netflix series! Music is an integral part of everyday life. Accordingly, musicologists work in a wide range of professional fields: The humanities degree in musicology provides students with the skills to open up new music-related professional fields.

A special feature of musicology and art studies research in Graz is the presence of a humanities faculty with a wide range of disciplines. Music as an art form is and has always been understood in relation to other art forms, media, cultural contexts and societies. The broad disciplinary diversity at the Graz location makes it possible to reflect on musical phenomena in the past and present comprehensively and in cooperation with partners from different disciplinary perspectives. This provides the basis for the development of innovative research perspectives, which ultimately also include the increasingly important potential of digital methods. Graz also has a diverse art and cultural scene - which is also easily accessible by bike at any time of day or night, thanks to the size of the city.

You have been a professor of translation studies at the University of Graz since 2020 and head the Translation and Digital Change research area. What has been the biggest challenge in your work since then?

To be honest, the biggest challenge so far has - unfortunately! - has not been one aspect of my research work. This is due to the fact that I have been Head of the Institute since March 2021, with the task of equipping the Institute of Translation Studies for the digital future. These and other organizational tasks, as well as the fact that I took over as head of the institute as an outsider right at the beginning of my employment, have proven to be the biggest challenges of my work to date. As far as research is concerned, I try to use my work to spark a critical debate on the use and social impact of language and translation technologies, for example with regard to the mostly unreflected use of ubiquitous machine translation in the public sphere today.

Among other things, you conduct research into issues such as the unequal global distribution of power, anti-democratic developments and the associated denial of global climate change. What is the connection between translation studies and such topics?

Translation studies is a discipline that has been firmly established for decades and sees itself as a link between the most diverse scientific fields. There are countless links, for example, to literature and linguistics, cultural and social sciences, but also to supposedly more remote fields such as computer and cognitive sciences.

At its core, this question relates to what we translation scholars call a translation-sociological problem. Translation, like all forms of communication, has a lot to do with power and ideology. When it comes to translation and interpreting processes, individual and group interests usually play a significant role. Translation actually always takes place via unequal power relations, usually to the detriment of the "weaker" party. At a concrete level, for example, community interpreting in asylum procedures in most countries is not yet professionalized to the extent that the concerns of asylum seekers can be negotiated in a translationally and ethically satisfactory manner.

On a global level, "strong" cultures - such as the Anglophone English-speaking world - tend to pay less attention to the cultural characteristics of other countries and cultures. This is often reflected in literary translations into English that ignore cultural differences. It is obvious how little foreign literature and culture is translated into hegemonic languages at all, especially into English. I myself refer to this problem as "hegemonic non-translation".

Furthermore, just imagine a re-elected President Trump establishing a flawless quasi-fascist dictatorship in North America. This would likely further cement the power imbalance between English and other languages, bring illiberal democracies to the fore worldwide, let alone stop climate change. In this context, it is the task of a translational sociologist not only to sense such developments, but also to point out that global cultural and linguistic diversity is just as central to the survival of human civilization as plant and species diversity, which is much more widely discussed in the media.

What is particularly important to you in your teaching - what do you want to pass on to students of translation studies?

University teaching is not just about acquiring specialist and specialized knowledge, but increasingly also about the ability to distill the essentials from a wide range of communication and information. This is particularly true of the translation and interpreting professions, where research skills play an important role, despite the apparent promise of communicative artificial intelligence! Students of translation studies gain a particularly intensive insight into the similarities and differences between cultures, languages and different forms of society. Through a scientific foundation, stays abroad and practical translation and interpreting work, you will be inspired not to view yourself and the world exclusively through monocultural, possibly even nationalistically colored glasses. If the students complete their studies with us with an open and open-minded, but at the same time interested and critical attitude, then I am already satisfied. Perhaps the only thing I can give them is to simply see themselves as human beings, nothing more and nothing less. Sometimes it's just a song that gives you hope again, for me it's Ziggy Marley's I am a Human. Just listen to it, translate it, spread it, ... if you want.

What would you say to someone who is interested in studying Slavic Studies at the University of Graz?

Even Ivo Andrić, the famous Yugoslavian Nobel Prize winner for literature, did his doctorate at the University of Graz. And if you want to find out what Russian bliny are, what the Slavs believed a thousand years ago and which Slavic language is the most romantic language in Europe, then studying Slavic Studies at the University of Graz is just the thing for you.

In addition, Styria borders on South Slavic countries and many students from these countries come to us - this provides easy opportunities to perfect these languages in conversation. The approach of the Institute of Slavic Studies and its researchers to Slavic cultures is also extremely diverse and enriching.

Which area within your field fascinates you the most and why?

The concept of the "(mysterious) Russian soul", which world-famous writers such as Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and Gogol talk about in their works, aroused my curiosity. Even the Soviet author Mikhail Aleksandrovich Šolochov said: "The greatest wealth of a people is its language. For thousands of years, the immeasurable treasures of human thought and experience have been gathered in words."

So I wanted to learn the Russian language in order to understand the mentality and thinking of Russian society and to unveil the mystery that surrounds the Russian soul.

You are studying for a Master's degree in Slavic Studies - are you planning to do a doctorate or do you already have your eye on a non-university field of work?

Due to my great passion for Slavic culture and language as well as my Slavic origins, I would like to be able to make a fundamental contribution to Slavic studies and also advance them.

For this reason, I am aiming for a doctorate in order to pursue an academic career. In my opinion, researching a subject that serves the general public is an enriching occupation.

When your friends or your family asks you: Why art history? What is your answer?

I have long enjoyed dealing with antiques but also with architectural styles, I like going to museums and visiting exhibitions, and after completing my studies I would like to work either in the auction trade or in the preservation of historical monuments. Above all, I also find it important to deal with ephemeral things and create awareness to preserve old values.

Which area within your subject fascinates you the most and why?

In general, I prefer to deal with the eras from the Renaissance to Historicism. In addition, I am interested in the areas of architectural stylistics and painting from these periods, as I find the details often found in Old Master paintings, as well as their painting techniques, fascinating.

You are currently studying for a bachelor's degree in art history, will you also pursue a master's degree?

Yes, I would also like to add a master's degree, although it is still uncertain whether it will be art history or another humanities subject.

What does someone actually do who deals with the history of science and why is it important at all?

As the term implies, the history of science deals, among other things, with the emergence and development of the sciences. I myself look at how the training of pharmacists developed in the early modern period, because unlike today, pharmacy was not yet a university subject but a teaching profession. To do this, I scour archives, libraries and museums for old manuscripts, pictures and anything else that can tell me something about it. Especially in times when health care plays a central role, it is always important to know the historical developments in more detail. Why is something the way it is today? I also report on this, among other things, on my Instagram channel @weltinderstube.

What is the fascination of your research field/dissertation for you?

History has fascinated me since I was a little kid! I find it totally exciting to read old letters or other things that people wrote several hundred years ago and held in their hands. I'm also an incredibly curious person and often wonder why things are actually the way they are today. A look at history can usually answer my questions.

You are an expert on curiosities, so to speak - what is the most curious thing that has ever happened to you at university?

As a first generation student, university and everything that goes with it was and still is somehow curious, strange, takes some getting used to. Which is not to say that I don't enjoy my time at the university. But especially at the beginning, you experience a lot of things that could be described as strange: People talk about other things differently, many things are unfamiliar to you, and you first have to find your place. That's how it is for many first generation students.

What exactly does a professor of Classics/Latin Studies do?

I am often asked what I actually do; the ancient texts from antiquity should all have been translated by now. In fact, we still translate texts today; because many books have not yet been translated, or the translations are outdated and can no longer convey the interesting statements of the texts in our present day. In many cases, the original sound of the texts must also first be laboriously determined. Above all, however, I would like to understand the texts and their style, interpret them, and discuss with students, colleagues, and anyone else who is interested what they once had to say and how we can understand it today. At the moment I am working on fables. Why does a wolf actually speak?

Does your heart belong to research or teaching?

I enjoy teaching very much; in particular, the lively discussions in the seminars, whether about Ovid's teachings on love or about Cicero's philosophy, are among the most gratifying moments in my profession. In the hustle and bustle of the semester, however, there is often no time to pursue one's research in depth; one can do that in one of the longed-for research semesters, and these are most satisfying times when one can devote oneself quietly to a question and arrive at a solution. But one finds after a while that one lacks the lively exchange. What has not been asked here is the third part of my work, the administration, which consumes immense time, threatens to become more and more, and is more the duty than the freestyle.

What is the funniest thing that has happened to you in the teaching room so far?

As a very young assistant in Leipzig shortly after the fall of the Wall, it was my job to retrain former Russian teachers to become Latin teachers - the average age felt to be 55. To explain the concept of captatio beneuolentiae, I quoted the beginning of a speech by Cicero, where he says - somewhat abbreviated -: "credo ego uos, iudices, mirari quid sit quod ego potissimum surrexerim, is qui neque aetate neque ingenio neque auctoritate sim cum his qui sedeant comparandus - I believe, you judges, you ask yourselves why I of all people have risen, who am not comparable in age, talent or authority to those who sit here." - Rarely has laughter been heard so loudly in this teaching hall.

Christina Hörzer

Department for Study and Examination Matters, Dean's Office of the Faculty of Humanities

What exactly do you do here?

I work at the Dean's Office of the Faculty of Humanities , where I am responsible for matters relating to studying and examinations My tasks are of a very diverse nature. From administrative support for students to website design, I am known at the faculty as the person you ask when you don't know what to do. Sometimes I have to comfort people, and sometimes I admonish them - whatever the situation calls for!

What do you like most about your work?

I am always engaged in new projects and very different tasks, which makes working at the Dean's Office very varied. It never gets boring!

What is the funniest thing you have experienced in the process?

Over the years, there have been a lot of laughs.... But I'd better not tell you most of it!

Klaus Kastberger

Professor for Modern Austrian Literature, Franz Nabl Department for Literary Research

You head the Franz Nabl Department for Literary Research and the Literaturhaus Graz, which is a wonderful combination of research, teaching and current literary activity. What is the most valuable thing about this job for you and your research?

My tasks here in Graz combine many different areas, but in an ideal scenario they all have a connection. One of the most beautiful moments I have experienced so far was when a student of mine was on her way out after an event in a packed Literaturhaus, and she said loudly and clearly and without any irony in my direction: "Thank you, Professor, for making us come to this event today!

How do you see the status of Austrian literature in the German-speaking world?

Perhaps, after decades of effort, we will soon be able to stop explaining Austrian literature to the Germans and presenting it year after year as a more exciting variant of German-language literature.

In the meantime, the Germans have become almost better acquainted with the supposed peculiarities of Austrian literature, and German authors make use of aesthetic patterns that we have hitherto taken as our own, as if it were a matter of course. Saying farewell to our past and embracing a future without aesthetic stubbornness could, however, be quite painful.

If the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Graz were a book, which would it be for you?

I cannot resist the temptation to immediately say The Man Without Qualities as an answer here. Musil worked on this novel for decades, and yet the book remained unfinished. Originally, the novel was supposed to clarify the preconditions that led to the outbreak of the First World War. Then the author was interrupted by the rise of National Socialism and the Second World War. The whole concept had to be transformed. Possibly, there is also a parable for humanities research here.

What exactly is your focus?

My research focuses on the philosophy of the early modern period, that is, the epoch in which the foundations of our present self-understanding were laid in many of its most important aspects. In my research, I also occasionally look back to the Middle Ages - a period that is sometimes underestimated in terms of its impact and diversity in philosophy.

What fascinates you most about your field? Or rather, what do you see as the value of the history of philosophy?

The history of philosophy can help us to discover our implicit prejudices and thus to look beyond our own presuppositions. Moreover, sometimes the old is just as good or even better than the new, and it is always instructive and helpful to improve one’s understanding of the past... and occasionally it is just fascinatingly quirky

What aspect of your work do you find particularly rewarding?

In particular, the opportunity to pass on my enthusiasm for the history of philosophy, and perhaps to encourage some students to do the same. I want to teach them to be open to the thoughts of others, as well as to understand the value of those thoughts.

What fields of work does your job actually involve exactly?

At our centre, I am involved with administrative tasks in the context of the university and the management of research projects and third-party funded projects. I represent the centre and the university in national and international working groups, professional associations, and research infrastructure projects on the topics of research data management, digital publication, curricula development, open science, and legal and ethical aspects of digital research. Copyright, licensing, and data protection in the context of digital scholarship are also my core teaching topics in our master's programme "Digital Humanities" as well as in our collaborative projects with internal and external partners.

Digital & Humanities - how do these two concepts fit together?

Actually, they fit together quite excellently. Thanks to progressive digitization and, above all, public accessibility of sources of global cultural heritage, we can research topics more extensively and in greater detail than was possible a generation ago. Ultimately, the humanities always explore artifacts of the human spirit and human culture - and since so much of what happens in society and culture today takes place in the digital realm, it is all the more important that researchers understand both humanities and cultural studies as well as digital methods and the associated ways of thinking.

What are the most common misconceptions that exist about Digital Humanities?

"Will you make me a website and a database?" is a question we still hear often today. Many still see computers as mere tools, think of a "digital publication" as a website, and think that digital humanities scholars are simply "programmers." Yet research-driven development and application of digital methods to digital sources is an extremely complex and ever-changing field that offers us ways of indexing, exploring, and, above all, communicating of our cultural heritage that could not have been imagined when I was a student - we can not only find previously unimaginable answers, but also ask previously unimaginable questions.

Why did you decide to study this subject in particular?

In the course of my undergraduate studies (Teacher Training Programme. Subjects: German and English), I developed a significant interest in linguistics. After graduation, I started looking for more ways to do computer-based research in this area. Instead of teaching myself programming skills through self-study, I tried the Master's program in Digital Humanities and then got 'hooked' on the field.

What was your favorite course and why?

Difficult to say, because actually all my courses were exciting. They dealt sometimes more theoretically, and sometimes more practically with the question of what digital transformation is doing to us, to the humanities and generally to our cultural heritage. If I had to choose, it would be the application-oriented VU Data Science (Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; SS2021), which was taught by Bernhard Geiger and Maximilian Toller in cooperation with the Know-Center/TU Graz. What I learned about data analysis and visualization helped me a lot in my master’s thesis and still helps me today in my work on the DiDip project.

What do you particularly like about Graz as a university location?

I think Graz is a pleasant mixture of city and country. Almost everything is easily accessible by bike. The location is also very diverse, whether it's culinary arts, the music and local scene, or events in general - it simply doesn't get boring. Apart from that, I like the location in the region, and in 2.5 hours you can make it to Vienna, or in 3.5 to the upper Adriatic.

What do you do at the Faculty of Humanities?

I am responsible for all administrative work at the Center for IInterdisciplinary Research on Aging and Care (CIRAC). And by that, I really mean all of it. From budget to project administration to the day-to-day business of office management.

What do you like most about your day-to-day work?

I always get to meet new and interesting people. I work with them on exciting projects whose content also interests me personally. And of course, the team in which I work!

What do you find particularly rewarding about your work?

Valuable friendships have developed over time with people from a wide variety of research fields and backgrounds.

Lara Wachter

Student, Teacher Training Programme. Subject: History, Social Studies and Political Education & Geography and Economics

Why did you decide to study this degree programme in particular?

During my school years, these were the two subjects in which my teachers particularly inspired me. In history, we worked with contemporary historical sources; it wasn't a matter of memorizing numbers and dates, but of understanding the subject. In geography, too, we talked about world politics and economics. I think that's important. I also want to empower young people to make good decisions. Especially in political education, it's not just about students knowing all the parties, but also why they should vote.

What has surprised or excited you the most in the course of your studies?

In geography, I was initially very surprised by everything that is part of this programme - human, physical and economic geography. In general, I was surprised at how different the areas are that are covered. In history, I was particularly impressed by Helmut Konrad's introductory lecture on contemporary history. When I listened to him, I knew: this is the right course for me. That's what I want to learn!

What do you particularly like about Graz as a university location?

I like the fact that everything is not too big here. It's easy to get to know your fellow students. You can also talk to the professors about problems on equal terms. That's really important! What's nice about campus life are the many small cafés and restaurants nearby and also the many green spaces that allow you to study or relax on warm days. The many study spaces that are available - especially in the new library - are also great!

What exactly does someone who studies German medieval studies do?

We deal with language and, above all, with the literature and culture of the Middle Ages (and their reception). What is particularly interesting about literary texts is that different discourses that preoccupied people at a particular time clash in them and not infrequently come into conflict with each other, are questioned, reconciled or modified. In our field, then, we ask ourselves primarily how a medieval text produces particular meanings by revealing its literary 'madeness' and the cultural assumptions that shaped it. This gives us revealing insights into an era that continues to fascinate many people to this day, as can be seen, for example, from the successful fantasy books, films, and series that continue to create medieval-like worlds.

You came to the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Graz from Heidelberg - how do you like it here, and what are the biggest differences?

I really like it here and feel very much at home. The city of Graz is beautiful and somehow already feels Mediterranean. Not everyone has the privilege of working and living in a place where others spend their vacations! And the university and the Department of German Studies also offer a varied working environment with extremely nice, open-minded colleagues who all work on interesting research areas. The biggest difference to Heidelberg is perhaps the size of the department. Although there are also many young people studying German here, there are very few staff with permanent contracts. On the other hand, there are also advantages of working together in a small group, because then you quickly get to know each other and people’s different research interests well.

What is the significance of medieval studies today?

When dealing with medieval literature - and this is also possible in German classes at school, for example - we are confronted with narrative worlds that are not part of people’s general experience today. This foreignness of pre-modern texts may at first seem to be a hurdle to understanding. But it is precisely the peculiar, irritatingly different ways of thinking and narrating in the texts that make us question what we take for granted and can trigger an examination of our own cultural and historical influence. The medieval world is foreign enough for us to question our habits of thought. At the same time, especially because of the language and the culture, it is close enough to be relevant for our social self-understanding. This can be seen not least in the above-mentioned popular fascination with medieval worlds, figures and mythical creatures such as knights, dragons and unicorns, which evidently people still identify with to this day and can be encountered not only in children's books but also in computer games and on packets of gummy bear - in other words, everywhere.